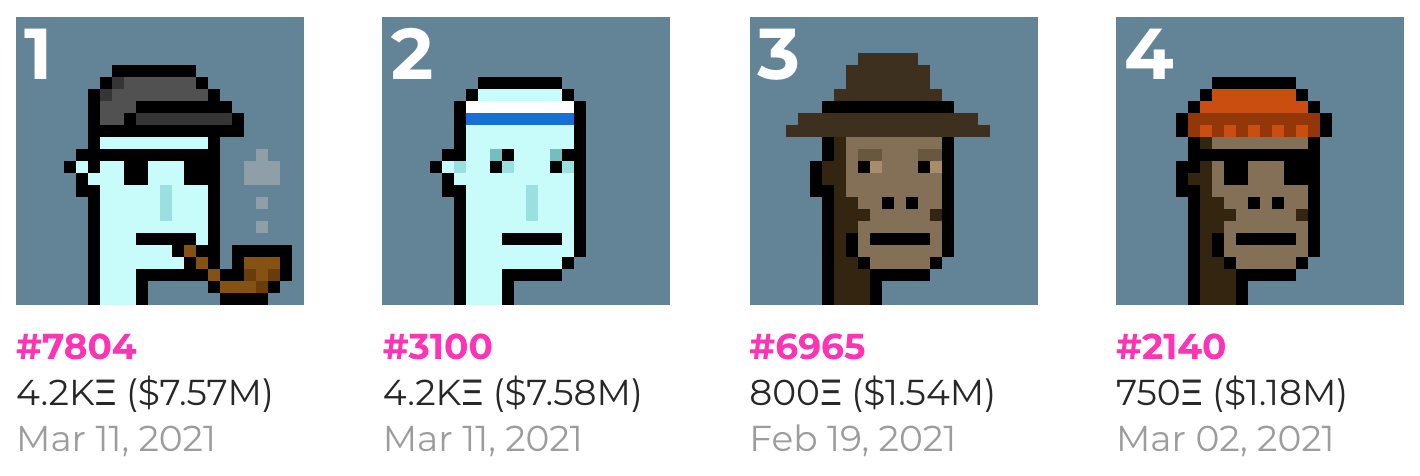

Live shot of vendorsplaining in action.Earlier today, my Twitter feed started buzzing with news of Ex Libris’ acquisition of Innovative Interfaces. Two historic library software competitors joining forces to make the best out of a rapidly declining financial situation. As a shareholder, this is exciting news. It’s probably requested by many. So

me would say it’s a win/win.

But what happens when those perspectives are projected onto the library community despite widespread evidence to the contrary?

Some Disclaimers

I typically stay out of ILS vendor and discovery debates. I spent 10 formative years of my career at two of the largest library software vendors in the world, including the one I’m writing about today. Even though I don’t own equity in any of them, or have a proverbial horse in the game, I still have biases that taint my view towards that market segment. So, I’m actually not interested in commenting on acquisition itself and its merits. I also know that in the coming days, many pundits will chime in on what may wind up being the second largest acquisition of the decade, only behind ProQuest’s acquisition of Ex Libris itself in 2015.

With that said, what I can’t get off of my mind is the way market consolidation writ large is discussed in the 2020 library landscape. The reason I take this personally is because it affects me and people I work with. I now work in an academic research library. I am also building a new kind of software company for libraries. While I don’t know what the future holds for me, I hope I remain in libraries in some fashion. And like others, I see some alarming things about the library community’s future if the status quo remains with regard to vendor relations.

There’s a blatant disconnect between how market activity is perceived and described by commercial vendors, versus how it is perceived and described by libraries. This disconnect is not just a matter of rhetoric. It lays bare the true opinions a vendor has towards the clients they serve.

Consider this blog post describing the III acquisition, which is presented as a more casual, personal take on the corporate press release that released earlier.

In the announcement, the executive writes that the acquisition is “exciting”, “requested by many”, and “for the common good.” He goes on to say that “it aligns with many emerging trends in our industry.”

Now, when I first read this, I laughed out loud. Mainly because it’s such a preposterous position to take in 2019. But as I wondered what would lead to a company to take this position publicly, I grew skeptical. The more I thought about it, there really aren’t that many options here:

- A) 🧢Dunce cap: The vendor believes the community lacks the critical thinking skills to notice the blatant falsehood of the statement in the face of myriad contradictory evidence

- B) 🐹Hamster on a treadmill: The vendor believes the community is too busy to recall statements made describing any number of past acquisitions, and how those statements never proved true

- C) 🌪️Kite in a Tornado: The vendor believes the library community has no options or strategy or challenge the power dynamic, and feels they can say whatever they’d like, however they’d like as a result

- D) 🍱All of the above

Regardless of which, it has become evident that their view of the library profession is one that utterly disregards its value, identity and purpose. Such distortion of reality for commercial gain is the institutional equivalent of mansplaining.

Let’s call it vendorsplaining.

Dwight Schrute being vendorsplained to.Vendorsplaining, coupled with the blatant disregard for the community’s desire for more choice, spells the single biggest threat to the information profession. Without a major shift in the way libraries procure products and services from third-parties, the foregone conclusion is the acquisition of the information profession itself.

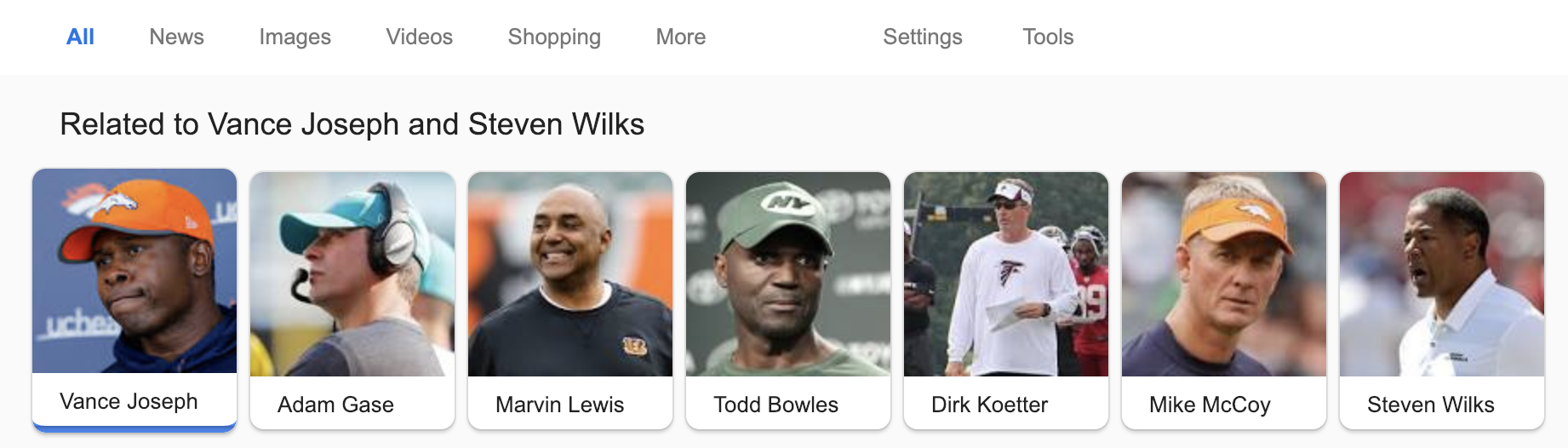

Another example comes from the keynote Elsevier’s new CEO’s delivered at Charleston. There was a segment where she shared her take on the various stakeholders in the scholarly community, along with what their roles were.

It was curious that in listing the community’s stakeholders (e.g. governments and funders, research leaders, researchers, and librarians), they didn’t include themselves, or commercial vendors writ large, as a stakeholder; which begs the question: Is it that Elsevier doesn’t see itself having a role in the scholarly ecosystem? Or is their worldview to replace one of the current stakeholders?

Let’s try this. Look at the slide above, and replace the word librarians for Elsevier. What do you see?

Now obviously, this is no admission of theirs. Call it a conspiracy theory if you want. But to me at least, it turns out that each bullet she listed for librarians tightly maps to things that Elsevier attempts to do today, or plans to do tomorrow:

- “Guard knowledge dissemination” ✅

- “Enable data management and reproducibility” ✅

- “Preserve and showcase intellectual outputs” ✅

- “Evolve assessment of research impact” ✅

- “Progress open access and open science” ✅

- “Manage Costs” ✅

If they are able to do these six things, then certainly they can make the case to our provosts and CIOs that they are able to solve the first bullet as well: “delivering universities’ mission”.

So, in this second example, how is it that a vendor can share plans that question the library profession’s existence in plain sight, yet facilitate such strong cognitive dissonance amongst listeners that we would wake up the next morning and settle for a “transformative deal” as a sign of hope? This is the power of vendorsplaining.

It bears repeating that vendorsplaining is not simply a matter of rhetoric. A vendor’s willful ignorance of data and anecdote in pursuit of increasing shareholder value is symptomatic of a deeper issue.

Whether in the context of industry consolidation or predatory publishing, the community would do well to call out vendorsplaining at every turn. Shrugging in the face of vendorsplaining is a surefire way to pave the profession’s path from existence, to endangerment, all the way to extinction.